The ship got her name on March 28, 1881, after Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy (or Dmitry of the Don), the Grand Prince of Vladimir. On that day Emperor Alexander III chose the names from the list for two semi-armored frigates — Dmitrii Donskoi, the lead ship of that two-ship series, which was built at the New Admiralty Shipyard, and Vladimir Monomakh, which was built at the Baltic Shipyard. The formal keel-laying ceremonies took place on both sides of the Neva River on May 9, 1881. On that day they attached the ‘silver laying tablets’ to the 43rd frame of the ships. Among the participants of the ceremony were the senior Navy officers including General Admiral Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich and the Head of the Navy Ministry Vice Admiral Alexei Peshchurov.

“The outfitting of Dmitrii Donskoi in Kronstadt had lasted for two years. In May 1885 they began testing the ship’s machinery and equipment, artillery armament and mine weapons, introduced some alterations and started remedial works. The works coincided with the preparations for the upcoming visit of Emperor Alexander III and a foreign voyage.”

Dmitrii Donskoi, the first Russian armored cruiser (semi-armored frigate), was launched on August 18, 1883, and became part of the Russian Navy in autumn 1885. Soon after that she sailed to the Mediterranean and remained there until 1887 being the flagship of a special naval unit. Then the vessel joined the Pacific Fleet under the command of Rear Admiral Alexei Kornilov.

In May 1889 the frigate returned to Kronstadt and was refitted there. Instead of the wooden spars they installed light metal tubular masts. They also had to deal with the severe hull fouling which affected the ship’s steel armor and copper sheathing. As a provisional measure during the ship’s stay in Nagasaki the armor’s surface was cleaned and covered with several coats of varnish. In Kronstadt they decided to provide the armor belt with the same protection as the underwater hull had.

On September 21, 1891, the ship began her second foreign cruise visiting many Mediterranean ports en route.Dmitrii Donskoi took charge of a detachment consisting of the frigate Minin, clipper Zabiyaka (Troublemaker) and the Black Sea-based gunboat Uralets (The Urals Native). In spring 1892 the detachment was disbanded and Dmitrii Donskoi sailed to Constantinople via the Sea of Marmara and then came to the Black Sea. In Batumi the ship was transferred under the command of Grand Duke Georgy Alexandrovich, brought the latter to Piraeus and then continued her voyage to the Far East

From July 1892 the cruiser remained in Vladivostok being the key force of the then small Pacific Fleet. Becoming the flagship after the departure of Vityaz to Petropavlovsk, in August Dmitrii Donskoi received guests from foreign ships.

In February 1893 the cruiser was ordered to sail to Port Said, where a new commander took charge of the ship: the Captain 1st rank Gessen was replaced by the Captain 1st rank Nikolai Zelenoy. At that time the United States government invited the Russian detachment to take part in the celebrations dedicated to the 400th Anniversary of the Discovery of America. Dmitrii Donskoi became the flagship of Rear Admiral Nikolai Kaznakov who commanded the Russian 1st naval division. The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia temporarily joined the crew of the ship (the latter took the position of the officer of the watch).

On March 16, 1893, Dmitrii Donskoi left harbor. On her way through Gibraltar the strong current seriously slowed the ship. Giving up the thoughts of making a transatlantic trip under steam power on schedule, the Captain of Dmitrii Donskoi ordered to proceed under sail. Alas, due to the prevalence of contrary winds the ship still failed to arrive at the meeting point of the international fleet on time and therefore made a beeline for New York (the other Russian cruisers General-Admiral and Rynda (Ship’s Bell) got to the meeting point on time). In New York Dmitrii Donskoi was saluted by thirty four ships that followed her. Donskoy took its place of a flagship in the Russian detachment; the ship’s officers spent all the time receiving guests and paying visits: the vessel was surrounded by the crowds of Americans.

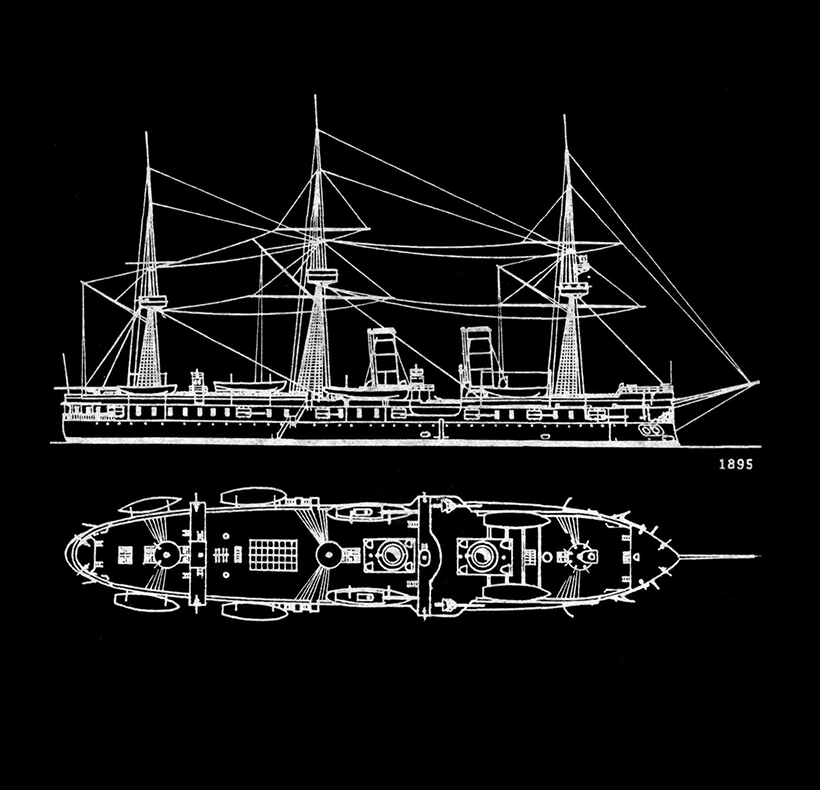

In September 1893, the cruiser returned to Russia. The ship’s worn engines and boilers required maintenance and replacement. In 1894 they completed the extensive repairs and in 1895 the ship was rearmed with six 152 mm and ten 120 mm Canet case guns.

Successfully passing the reception tests, on October 29, 1895, Dmitrii Donskoi and the newest cruiser of the class Rurik left for Mediterranean to deal with a possible threat from England.

On February 14, 1896, the ships set a course for the Far East and arrived at Nagasaki on April 9. That time Dmitrii Donskoi spent six years in the Pacific Ocean. On October 7, 1897, she became the first vessel to enter the new dry dock in Vladivostok, and in March first visited Port Arthur “leased” from China a short while ago. In 1900 Dmitrii Donskoi took part in large-scale naval and land exercises that transformed in actual combat when the violent Boxer Rebellion erupted on the territory of China.

On December 12, 1901, Dmitrii Donskoi left Port Arthur with Captain 1st rank M.I. Wander-Shkruf in command. The cruiser arrived at Kronstadt being part of an armored detachment which flew the flag of Rear Admiral G.P. Chukhnin. There she was refitted again into a gunnery drill ship for the Pacific Fleet: six of her ten 120 mm guns were replaced by 75 mm guns; small-caliber weapons were refitted too.

In 1903 the cruisers Dmitrii Donskoi and Almaz (Diamond) were assigned to convoy a squadron of destroyers, but the preparations dragged on and as a result the ship joined the special detachment headed by Rear Admiral A.A. Virenius. The authorities of the Naval Ministry hindered the movement of the detachment, and by the beginning of the Russo-Japanese war Dmitrii Donskoi managed to pass the Red Sea only, and after that received an order to sail back to Russia. The ship’s commander Captain 1st rank L.F. Dobrotvorsky began to capture military Japan-bound cargos without authorization from the superior echelons. He had managed to seize three steam ships before he got a strict order from the General Naval Staff to set the arrested ships free.

In 1904 Dmitrii Donskoi (under the command of the Captain 1st rank Ivan Lebedev) became part of the 2nd Pacific Squadron flying the flag of Vice Admiral Z.P. Rozhdestvensky. Together with the squadron the ship passed the Cape of Good Hope, and on May 14, 1905, she went into action in the Korea Strait, being part of the detachment of cruisers under the command of Rear Admiral Oscar Enkvist.

In the course of the battle when the cruiser Aurora’s steering system went wrong, Dmitrii Donskoi and Monomakh shielded her with their hulls, thus coming under a fire from the Japanese fleet. Returning fire the veteran Russian cruisers managed to cause damage to several enemy ships. That gave the chance to the fast moving Oleg, Zhemchug (Pearl) and Aurora (which had undergone urgent repairs) to put on full speed and disengage from action. The slow-moving Dmitrii Donskoi was left unsupported but still managed to avoid the attacks of the enemy destroyers, and when night fell she made her way towards Vladivostok at a rate of nine knots and keeping the lights off.

Of all squadron’s capital ships Dmitrii Donskoi managed to get as near to Vladivostok as possible. When the cruiser dropped anchor near the Dagelet Island in the Sea of Japan to save the crew of the sinking destroyer Byiny (Fast and furious) she encountered the pursuing Japanese ships. Six fast-moving cruisers (Naniwa, Takachiho, Akashi, Tsushima, Otowa and Niitaka) and four destroyers surrounded the ship. Dmitrii Donskoi refused to surrender and while firing back managed to damage two enemy cruisers (Naniwa and Otowa), but was critically damaged as well. The ship could not continue its way as the pumps could not handle the flow of water coming through the holes in the hull. At night they managed to evacuate the crew and the fatally wounded captain (he died in a few days after being captured) from the ship to the island, and in the morning the cruiser went down never hauling down the flag.

The project is dedicated to a good friend of ROSPHOTO Konstantin Petrovich Guber (01.01.1960–07.02.2016) who time and again provided invaluable assistance in attributing naval collections. Many earlier unidentified subjects and characters have been “deciphered and defined” thanks to the patience and efforts of Konstantin Guber.

A graduate of the Leningrad State Pedagogical Institute, Konstantin Guber in 1985 got a job at the Central Navy Museum. He dedicated his life to the museum where he had worked for thirty years. He first worked as an interior designer, and then from 1986 to 1993 he was the head of the museum’s photo laboratory and closely collaborated with the photo negatives fund. He had been the head of the museum collection department for eight years. From 2001 he held the position of the Central Navy Museum’s art director and in 2009 became the curator of the country’s largest collection of photographic documents on maritime history. Guber was the author of a wide range of articles in such miscellanies as Maritime Photography, Photograph. Image. Document and others.

The amateur photography was booming in Russia in the 1880s. They began photographing the foreign voyages of Russian fleet in detail from the mid 1880s. The routes of the ships often intercrossed, and the sailors during the stay in the ports used to exchange pictures with each other or buy photographs in the local photo studios. In this album one can see the photographs by Nikolai Apostoli, who sailed aboard the cruiser Nayezdnik (Rider) at that time, as well as the pictures by his cousin, novice photographer Alexei Butakov. Some of the featured photographs were created by the renowned photographer Hyppolyte Arnoux who then worked in Port Said. There are also some pictures by other photographers of the age, although their provenance is yet unknown.

kp082_083.jpg Captain Nikolai Apostoli (1861–1937) was the founder of maritime photography, publisher of postcards and photographer of Russian fleet.

He first tried his hand at photography in December 1886, when he bought his first photo camera during the stay of the clipper Nayezdnik in Rio de Janeiro. The most famous works by Apostoli were created during Nayezdnik’s round-the-world voyage (1886–89): the photographs of the major part of the Russian ships of the late 19th – early 20th centuries (including underwater and stereo photographs). His works dating from the 1890s are less known: among them are the pictures that cover the maritime everyday life and the photo reports dedicated to the celebration of the Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus and to the inauguration of the Kiel Canal. After the Revolution of 1917 Apostoli was the head of the photo laboratory of the Baltic Fleet’s Political Directorate, then he was in charge of the photo technical laboratory of the Leningrad History Museum and also taught photography at the Frunze Naval Academy. He retired from service in 1930 and died of a serious illness in 1937 in Leningrad.

He was awarded the Order of St. Stanislaus 2nd class, the Order of St. Anna 2nd class, the Order of St. Vladimir 4th class (for his 25-years-long officer service). Apostoli was the author of the books A Guide on the Studying of Applied Photography for Navy Officers and Tourists (1893) and A Popular Guide on Photography for Beginners (1915). He worked on two-lens cameras, telephoto lens, and on a camera for underwater shooting.Alexei Butakov (1862–1921), Vice Admiral, son of Grigory Butakov (1820–1882), Admiral, theoretician of steam-driven Navy forces, a member of the State Council, and brother of Rear Admiral Alexander Butakov (1861–1917).

Hippolyte Arnoux (ca. 1860 – ca. 1890) was a French photographer and publisher. In the 1860s he worked in Egypt in his photo studio in Port Said. He photographed Egyptian ancient monuments, sights of Cairo, but his most important work was dedicated to the construction of the Suez Canal. He published the resulting photographs as Album du Canal de Suez. Port-Saïd.

Hippolyte Arnoux was also known for his open-air genre pictures and ethnographic studio portraits of young women, mainly. In the late 1860s he collaborated with Antonio Beato.